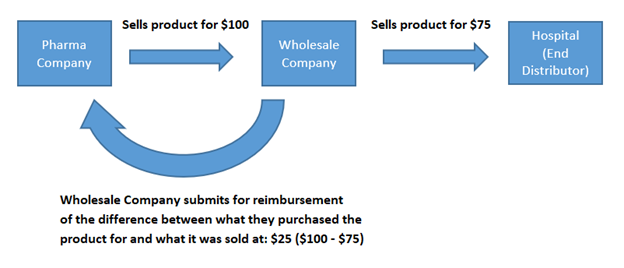

Chargebacks previously explained in our article titled, “What Are Chargebacks, and Why Are They Important?” are contracts between wholesale customers and pharmaceutical companies designed to reimburse wholesalers between the gross sales price at which a pharmaceutical company sells its products to the wholesalers, otherwise known as wholesale acquisition cost (WAC), and the prices of the products charged at the time of resale by the wholesaler to the end distributor (pharmacy, hospital, etc.). The difference that is reimbursed is known as a chargeback.

Example of a chargeback:

Chargebacks represent the single most significant deduction from gross sales for most pharmaceutical companies and, in most cases, estimates (accruals) utilized for financial statement purposes. So, from a tax perspective, how does a taxpayer determine if these accruals are deductible?

Accrued expenses are generally deductible for tax purposes when all three Internal Revenue Code (IRC) 461 tests have been completed. These tests are collectively known as the “All-Events Test,” and each prong of the test has specific nuances, of which a few are detailed below:

- All the events have occurred that establish the fact of the liability.

- Generally, the occurrence of the All-Events Test is when the event fixing the liability occurs, whether that be the required performance or other event, occurs, or payment therefore is due, whichever happens earlier. Additionally, liability is only “fixed” if it is not subject to any conditions or contingencies that prevent the taxpayer from having a recognized, existing liability.

- The amount of the liability can be determined with reasonable accuracy, and

- The amount of an accrued liability does not need to be exact. Rather, a reasonable accuracy methodology is applied, and if a sound basis of computation supports the estimate, the expense would be deductible.

- Economic performance has occurred with respect to the liability.

- Economic performance with respect to a liability to pay a rebate, refund, or similar payment occurs as payment is made to the person to whom the liability is owed. Since unique fact patterns are present in every transaction, often a taxpayer relies on deducting accruals via the “recurring item exception,” whereby the liability can generally be expected to be incurred from one year to the next.

WG observation: Our experience is that analyzing the All-Events Test for chargebacks is crucial for year-end tax reporting. Since GAAP financials will report an accrual for chargebacks, the deduction is limited to the extent of the three-pronged test referenced above. From a practical standpoint, it is challenging to meet the requirement that a liability is “fixed and determinable” if the product hasn’t yet been sold to the end distributor. For example, if a pharmaceutical company sells a product close to year-end and that product remains unsold by the wholesaler, the pharmaceutical company may book a “reasonable” accrual for the expected chargeback; however, supporting the amount of the liability is key for taking a deduction. Whatever method is chosen, we suggest remaining consistent so that future accruals may fall under the recurring item exception rule.